THE CELTS AND THEIR BELIEFS

Celtic

people were at one time all over Europe, from the British Isles in the west, to

even as far as what is now Turkey in the East. They were not a single unified

race, and lived in tribes or clans with their own chief or king. The ancient Greeks

coined the name ' Keltoi' to refer to, as they saw them, their mysterious neighbours.

It meant "hidden/secretive people", probably because they did not live

in stone towns or cities like the Greeks, preferring forts, villages and camps

in more natural environments.

Celtic

people were at one time all over Europe, from the British Isles in the west, to

even as far as what is now Turkey in the East. They were not a single unified

race, and lived in tribes or clans with their own chief or king. The ancient Greeks

coined the name ' Keltoi' to refer to, as they saw them, their mysterious neighbours.

It meant "hidden/secretive people", probably because they did not live

in stone towns or cities like the Greeks, preferring forts, villages and camps

in more natural environments.

To these people there were many sacred places in the living landscape. The ancient Celts revered nature and the elements, and worshipped the sun, moon, the stars and the Earth Mother, with a wide range of goddesses and gods. They celebrated their deities, ancestors, life, the natural world and its creatures, and the changing of the seasons through their music, poetry, story telling and art. Their poets and musicians, the Bards, and their wise holy men, the Druids, were very high up in the social hierarchy of the tribe, training for many years in their orally learnt crafts, as nothing was written down. Their artisans were also well respected, and were stone carvers, wood and metal workers.

They created fabulous works of art in the form of stone monuments, also metal jewellery, weapons and armour, often inlaid with bright enamels. An often over looked art was that of tattooing, although we have no records of exact designs, we do have contemporary descriptions of tattooed Celtic warriors, written by Roman observers, who made a distinction between permanent tattoo symbols, and the also common use of blue woad as warpaint. Go to the Celtic Art page for an article on ancient tattoo, by Hamish and his brother Dudley.

The warriors were fearless due to the Celtic fact that the spirit is immortal - to die was an accepted fact of life - no matter, because you would be reborn again. Things that are mystery and fantasy to the modern world were accepted fact in ancient Celtic times - that is, the existence of strange beasts, giants, and little people, and of course the Otherworld. The Otherworld existed alongside and connected to our own, a place of eternal happiness and immortality, to which mortals could cross at certain times of the year, and through special natural places such as hilltops, caves, waterfalls, riverbanks and other sacred places. Days in the Otherworld were said to run as years in the mortal world, so returning was another story...

History and myth are mingled in early Celtic times. Ancient Irish manuscripts, the 'Book of Invasions' say that 5 groups of invaders arrived before the Celtic Gaels. Cessair was descended from Noah, and after her father Bith was denied a place in the ark, they sailed a ship for 7 years, until the Cessair arrived in Ireland 40 days before Great Flood. Only one of her tribe, Fintan, the White Ancient, survived the deluge.

The Partholons arrived next, and battled the Fomorian warlike residents, winning posession of the island for 300 years, until destroyed by plague.

Next were the Nemedians (possibly of Greek or Scythian origin), who beat the Fomorians several times, but were decimated by plague, and were finally were defeated by their foes. Among those that escaped was a Nemedian warrior, Briotan said to have given his name to the island and people of Briton.

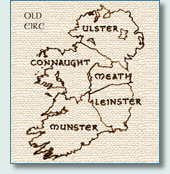

Descended from the Nemedians

were the next wave, the Fir Bolg, who divided the old land into 5 provinces, Leinster,

Meath, Connaught, Ulster and Munster. Meath later merged with Leinster.

Descended from the Nemedians

were the next wave, the Fir Bolg, who divided the old land into 5 provinces, Leinster,

Meath, Connaught, Ulster and Munster. Meath later merged with Leinster.

The following invasion was by a mystical race known as the Tuatha de Danann (the children of Dana), said to have arrived from the sky, after wandering Europe and at one time residing in Alba (Scotland). They were a beautiful, artistic warrior race, descended from the Nemedians, and achieved god-like status in Irish mythology.

They arrived with 4 magical treasures, the 'Lia Fail' (Stone of Destiny), the 'Spear of Lugh', the 'Sword of Nuada' and the 'Cauldron of the Dagda'. The Tuatha de Danann defeated the Fir Bolg at the First Battle of Moy Tura, only to return there later to fight the ancient enemy, the Fomorians, at the Second Battle of Moy Tura, led by King Nuada of the Silver Arm and their warrior hero Lugh the Il-Dana. Nauda was slain, and so was the Fomorian king, Balor of the Evil Eye, by his own grandson, Lugh, forever ending Fomorian power. Lugh was said to have first arrived to his people with a 'fairy host', who had fostered him in his youth.

The Tuatha de Danann ruled Ireland for 197 years, their main residences being in the Boyne Valley, where the ancient megalithic tombs of Newgrange, Knowth and Dowth stand.

Newgrange megalithic tomb, Co.Meath

The next invasion was by the Milesians, of whom the descendants were the Gaelic Irish. Although they beat the Tuatha in battle and settled, mysterious blights on their land and animals forced them to allow the Tuatha de Danann to remain in Ireland, however this magical race retreated to their 'sidh' or 'fairy mounds', and other special natural places in the landscape, where they are still said to live today. Lugh's name lived on into Celtic times as the festival of Lughnasadh, and it is said that at Samhain, modern day Halloween, mortals could access the Celtic Otherworld through these places, to reach the Land of Tir-na-nOg, the Land of Youth.

From these narratives come the legends of 'little people', in all the Celtic Lands, in the form of the sidh ('banshee' is from a Scots term for a wailing spirit being), fairies, leprechauns, pixies, piskies, brownies, knockers, and others.

The ancient Celts lives were arranged to follow the seasons, and their calendar fixed by the Druids followed the passage ot the stars and moon, as shown by the bronze Gaulish calendar tablet found in France at Coligny (in 1897), dating from the 1st century AD. The Celtic day started at sunset, so did their celebrations.

The start of each season was marked by a major festival, starting with the Celtic New Year on the eve of November 1st, SAMHAIN (pronounced 'sha-ven' or 'sow-en' depending where you were), the Celtic Feast of the Dead, or the feast to the dying sun, marked the beginning of Winter, with the harvesting finished and the start of stockpiling fuel and produce. Bonfires were lit, and household fires extinguished to be rekindled later from the ceremonial fires, to welcome returning souls of the dead. Young folk would jump thru the fires to cleanse themselves for the new year, or run sunwise around the fire, getting closer each time till it became too hot, the bravest having the best luck in the coming year.

The ancient Druids believed the Lord of Death, Saman, gathered together evil souls, and so the Irish called this evening Oiche Samhna (The Vigil of Saman). In Manx it was Savin , or Hop Tu Naa (this is the night), and in Welsh it was Nos Galan Gaeaf (winter's eve), and in Breton it was Nos Kentan 'r Bloaz (the first night of the year). The goddess Bride or Brigit, ended her ruling season, and her straw crosses were put up to proect family and livestock. In Scotland, Cailleach Bheur, goddess of winter, began her reign.

'SAMHAIN' © Hamish Burgess 2010

The Celts believed on that night between the passing of the old year, and the arrival of the new, that the veil between our world and the Otherworld (or spirit world) was thinnest, and that spirits and faerie folk could visit the human world, and vice versa, and that you could contact your passed ancestors. That belief has continued with today's Halloween traditions of witches and ghosts, etc.

The Christian church called the festival 'The Feast of all Saints', on 'All Saints' Eve' or 'All Hallows' Eve', hence the term "Hallowe'en".

The tradition of children 'trick or treating' possibly came from the ancient practise of 'soul caking', when children went round collecting cakes in return for saying prayers for the dead. In later times, children wore masks and carried turnip or pumpkin lanterns, going door to door asking for apples, nuts or money, the disguises originally to stop them being recognised and taken by spirits.

The tradition of a turnip lantern, or more popular today, the "Jack O' Lantern" carved pumpkin, actually comes from the ancient Celtic practice of placing skulls of the dead on poles around the encampment, to drive away evil spirits.

The winter months of November, December and January are divided by the Winter Solstice

on December 21st. The Winter Solstice was a celebration of the rising of the sun from

it's lowest point in the sky, back to longer days and the lighter part of the year.

The sleeping earth was heading toward re-awakening. Evergreen trees were seen as a

reminder that spring would bring re-birth. Druids ceremoniously cut mistletoe, and

offerings were made to the Gods for the return of the Sun. Mistletoe was sacred,

and as well as an antidote for poisons, had a fertility connection, carried on to

this day as the tradition of "kissing under the mistletoe".

The Gaulish Druids called their month of November-December "Dumanios", or 'The Darkest Depths'.

Next was the festival of IMBOLC on the eve of February 1st, marking the beginning of Spring, associated with the goddess Brighid, Brigit, or Bride, divinity of healing and childbirth, smithcraft and the hearth. Brighid is an important link between the Old Ways and the Celtic Christian church, and the hearth tradition continued in the form of St. Brigit of Kildare, who founded a monastery there, where a sacred flame, tended by nuns, burnt continuously from the 5th century until the Reformation, hundreds of years later. In Ireland, her tradition continues at Imbolc time to this day, with woven wicker-work crosses, "Brigit's Crosses", being hung by doorways.

“IMBOLC” © Hamish Burgess 2011

The spring months of February, March and April, are divided by the Spring Equinox on March 21st.

Following on was BELTANE, a May Day eve festival, dedicated to Bel (also called Beli and Belinus), the sun god, marking the beginning of Summer. Beltane means 'the fires of Bel'. In ancient times, Druids would kindle the Beltane fire, and two seperate bonfires were made, with poeple and animals being driven between them, to cleanse them of diseases and bad luck form the dark part of the year, winter. Household hearths were re-lit from the Beltane fire, having been extinguished for the occasion. The festival tradition has continued to this day in Britain and Ireland, in the form of May Day celebrations.

“BELTAINE” © Hamish Burgess 2011

The summer months of May, June and July are divided by 'Alban Heruin', the Summer Solstice, on June 21st, with the longest day of the year (in the Northern hemisphere). It is also referred to as Midsummer because it is roughly the middle of the growing season throughout much of Europe. Many remains of ancient stone structures can be found throughout Europe, some of which align on the midsummer sunrise.

According to the ancient Gaulish tablets, the Coligny calendar, the time of June / July was called "Equos", or 'horse-time', a time for fairs and good weather. In ancient Gaul the Midsummer celebration was called Feast of Epona, named after a horse goddess who personified fertility, sovereignty and agriculture. She was portrayed as a woman riding a mare.

Druids celebrated Alban Heruin ("Light of the Shore") and led the ancient Celts in homage to the Sun. The days following Alban Heruin form the waning part of the year because the days become shorter. To signify this, a descendant of an ancient ritual was to wrap a cartwheel with straw, set it alight, and roll it down a hill. Young children would spend the day weaving discs of vines, to light that evening and hurl into the sky, or roll down hills.

In Penzance, Cornwall, the Golowan Festival or Feast of St.John takes place, with musical processions through the old town down to the harbour led by Penglaze, the Obby Oss.

Closing the cycle was LUGHNASADH, the Harvest festival (Lunasa in modern Irish), starting on the eve before August 1st, the beginning of Autumn or Fall. Named after the god Lugh, "The Bright or Shining One", a Celtic Sun God, and God of the Harvest, who also presides over the arts and sciences, as he was called Lugh the Il-Dana, "Master of All Crafts" (also Lugh Llamfadha 'the long-handed', Samildanach 'he of the many gifts', Lug, Lugaidh, Lleu, and Llud).

“LUGHNASADH” © Hamish Burgess 2011

In Irish history, Lugh's mother was Eithne, Fomorian daughter of Balor, and his father was Cian of the Tuatha De Danann. In legend it was foretold that he would kill his grandfather, so his mother, afraid for his life, fostered him to Tailtiu, Queen of the Fir Bolg, and later to the Sidh of the Sea God, Manannan Mac Lir, on the Isle of Man. He became a famous warrior of the Tuatha De Danann, fulfilling the prophecy and killed his grandfather, Balor of the Evil Eye at the Battle of Moy Tura, winning the day for the Tuatha.

Lughnasadh means 'the binding duty of Lugh', referring to funeral

games he held in honour of his foster-mother Tailtiu, a goddess of agriculture. It is said that she died from exhaustion after clearing a great forest so that the land could be cultivated, and on her death-bed she told the men of Ireland to hold funeral games in her honor - she prophesied that as long as they were held Ireland would not be without song. Many summer fairs and festivals today come from this tradition.

Lughnasadh continued through the harvest time, not necessarily just one night,

as crops were harvested in August, fruit in September, and meat in October. The

autumn months of August, September and October are divided by the Autumn Equinox

on September 21st.

It may seem odd to start the year in November, but to the Celts it was a significant time, when the years labours had been harvested, and the ground was ready for winter planting.

The ancient Celts were a flamboyant people, who loved festivals and feasting, with much drinking, music and story-telling. The Bardic tradition has survived to this day, being an important link to the past. They also had Satirists, who were, like the Bards and Druids, high up in Celtic society, whose witty but often scathing prose could cost even a chief to fall out of favour. This trait has survived in some of the descendants of these people as sarcastic humour, often sadly misunderstood by other races, as has the liking for "a good old drink and a yarn".

They

favoured brightly coloured clothes, with stripes and checked patterns, the checked

material carried on today as the tartans (plaid) of Scotland and Ireland. They

had fine jewellery in the form of neck torcs, bangles, rings and brooches, intricately

decorated with their artwork, as were their weapons and armour, often inlaid with

bright enamels. Their art had a purpose, normally functional, but also often to

impress neighbouring tribes.

They

favoured brightly coloured clothes, with stripes and checked patterns, the checked

material carried on today as the tartans (plaid) of Scotland and Ireland. They

had fine jewellery in the form of neck torcs, bangles, rings and brooches, intricately

decorated with their artwork, as were their weapons and armour, often inlaid with

bright enamels. Their art had a purpose, normally functional, but also often to

impress neighbouring tribes.

The

Celts were skilled horsemen, and revered their animals in the form of the horse

goddess Epona, who was often featured on their coins. They were one of the first

races to fight on horseback, even making armour for their mounts, and the Celtic

cavalry was feared across Europe. They are said to have invented the spoked wheel,

and were renowned for their use of their invention the chariot, fighting from it and as noted

by amazed Roman historians, running out along the harness beam while at full speed.

They worshipped a triple-aspected goddess, the Morrigan, seen as Anu, Macha, and

Badb, and were often seen fighting in threes. The number three was sacred to the

ancient Celts, symbolic of life, death, and re-birth which was a matter of fact

to them. Many of the ancient burial mounds contain 3 chambers, and their art often

used configurations of three, a common ancient symbol being the triscele. The

triple aspect of the mind, body and spirit is still represented today in many

religions.

The

Celts were skilled horsemen, and revered their animals in the form of the horse

goddess Epona, who was often featured on their coins. They were one of the first

races to fight on horseback, even making armour for their mounts, and the Celtic

cavalry was feared across Europe. They are said to have invented the spoked wheel,

and were renowned for their use of their invention the chariot, fighting from it and as noted

by amazed Roman historians, running out along the harness beam while at full speed.

They worshipped a triple-aspected goddess, the Morrigan, seen as Anu, Macha, and

Badb, and were often seen fighting in threes. The number three was sacred to the

ancient Celts, symbolic of life, death, and re-birth which was a matter of fact

to them. Many of the ancient burial mounds contain 3 chambers, and their art often

used configurations of three, a common ancient symbol being the triscele. The

triple aspect of the mind, body and spirit is still represented today in many

religions.

As each Celtic language had different spellings, and as they had many goddesses and gods, it is impossible to list them all, but important godesses were the mother goddess Danu (Anu, Ana or Don), with her darker side as the Morrigan, and her sister Brigid (Bride or Brigit), associated with the home, hearth, animals, wells, childbirth and healing. Gods included Dagda, "The Good God", god of druidry, Cernunnos, god of nature, animals and hunting (who would later reappear as the Green Man), Lugh the sun god, Manannan the sea god, and Bel. Their priests were the Druids, who were also healers, poets, philosophers, judges and prophets. All druids were bards, but not all bards went on to become druids, as the learning could take 20 years. It was said they could shape-change into animals.They had no written records, but a system of marks that equated to letters, called Ogham, normally carved on memorial stones and markers. The marks also corresponded to the trees, which were an important part of the Druidic lore. the Ogham stones can still be seen in the Celtic lands today, most commonly in Ireland and Scotland.

As female and male gods had equal status, so did men and women in Celtic society. Women could be warriors, and great queens, such as Meave in Ireland and Boudicca (Boadicea) in Britain, who led a massive revolt against the Romans.

Queen Boudicca statue in London

From the 2nd century A.D., the Old Ways were slowly absorbed by the new religion of Christianity, the monks being careful to incorporate ancient long held beliefs into Christian teachings, in order to convert the people. Old celebration days became Church days (Samhain became All Saints Day, Imbolc now St. Brigid's Day, Beltane is now Whitsun, and Lughnasadh is Lammas), old sacred places became the sites of churches, and even variants of old gods and goddesses ended up as Christian Saints. For several centuries monks journeyed across the islands spreading their faith, many of these men and women, hundreds of years later, also destined to be made Saints.

Irish High Cross at Kildare

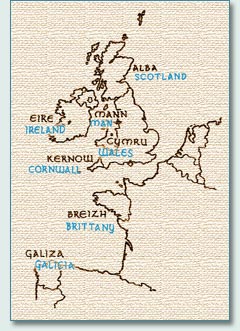

These monks of early medieval times became the next wave of Celtic artists. They took the early artform of interlaced knotwork, probably originated earlier in the stonework of the Picts in what is now called Scotland, and refined it in fabulous illuminated manuscripts, versions of the Gospels, and while converting the ancient people to their new religion, founded monasteries and spread their amazing artwork through the Celtic Lands of Scotland, Ireland, Wales, the Isle of Man, Cornwall, Brittany and Galicia.